Since the early stages the profession of dietetics has been characterized as a multifaceted discipline and influenced by scientific and social changes. Today, health and nutrition-related diseases are becoming more global - as is the dietetics profession. The aim of this article is to review the history, education, work and challenges for dietetic practitioners in North and South America, specifically in the United States and in the Argentinean Republic. It was in Argentina where the first Latin American dietetics school was established. Both countries have since shaped the profession creating standards for education and practice in response to advances in the biopsychosocial sciences and economic and environmental changes. Reviewing both the past and current diversities in both Americas contributes to a better understanding of professional strengths and weaknesses, and can prepare dietetics specialists to meet today’s needs. Regardless of local disparities, it is interesting that current and future challenges for the dietetics profession are similar between the two countries, such as growing rates of obesity, limited access to and choice of healthy diets among various income groups, busy lifestyles and decline of family meals. These common issues and the availability of Internet tools offer a unique opportunity for partnership and research that can lead to successful creative nutrition interventions and programs. In turn, such joint initiatives will confirm the essential role for the profession – not only in the western hemisphere – but also globally.

Key words: International dietetics, dietetics evolution, dietetics in Argentina, dietetics manpower.

Desde sus comienzos la dietética ha sido caracterizada como una profesión multifacética e influenciada por cambios científicos y sociales. Actualmente las enfermedades relacionadas a la nutrición se están convirtiendo en asuntos globales, como así también la profesión. El objetivo de este artículo es contrastar la historia, educación, ejercicio y desafíos de la profesión entre Norte y Sur América, específicamente entre Estados Unidos de América y la República Argentina. Fue en Argentina donde se estableció la primera escuela de dietética de Latinoamérica. Desde entonces, cada país ha dado forma a la profesión, creando estándares para la educación y el ejercicio profesional en respuesta a los avances científicos, socioeconómicos y ambientales. El análisis de la historia de la profesión y de su diversidad contribuye a un mejor entendimiento de sus fortalezas y debilidades, y a preparar a los nutricionistas para satisfacer las necesidades de hoy. A pesar de las diferencias regionales, existen desafíos actuales y futuros para la nutrición y dietética que son similares entre los dos países analizados, tales como el incremento de la prevalencia de obesidad, el acceso limitado a dietas saludables en grupos de diferente nivel socioeconómico, el estilo de vida moderno y la depreciación de comidas en el hogar. Estos desafíos en común y la disponibilidad de Internet ofrecen una oportunidad única para el trabajo en colaboración y para el desarrollo de intervenciones nutricionales efectivas. En definitiva, estas iniciativas conjuntas confirmarán el rol esencial de los nutricionistas – no solo en el hemisferio occidental – sino también a nivel global.

Palabras clave: Dietética internacional, historia de la nutrición, nutrición en Argentina, recursos humanos en nutrición.

Centro de Educación Médica e Investigaciones Clínicas “Norberto Quirno”, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Clinical Dietetics.

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Dietetic professionals are now present in many countries on every continent. Each country has its own qualifications for academic and professional education and may differ in the scope of their nutrition practices (1). Information about dietetics practice in the United States is readily available and accessible through the Internet, but little data have been published about the work of dietitians in Latin America (2).

The first dietetics school in this region was established in Argentina (3-6), where the profession is today showing important signs of growth (7). The purpose of this article is to review the similarities and differences in dietetics education and practice in the western hemisphere, linking past, present and future of the profession between two countries: the United States of America (US) and the Argentinean Republic. Standard research methods were used: review and critical reflection on texts and journals.

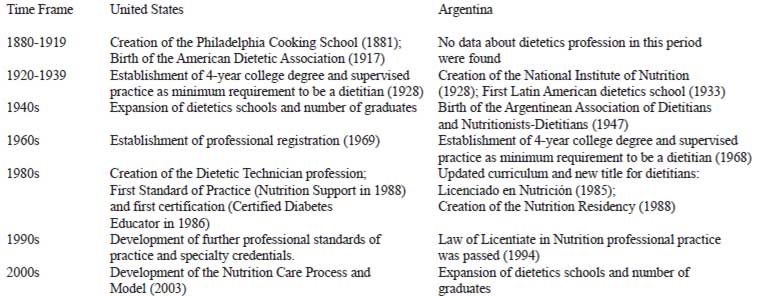

The first US dietitian was Sarah Tyson Rorer (1849-1937), who founded the Philadelphia Cooking School in 1881, started a diet kitchen for patients with physician-ordered diet prescriptions, and provided training for physicians in dietetics. The dietitian’s sphere of influence in the late 1800s and early 1900s was limited to the “feeding of the sick”, the instruction of physicians and nurses, and the prevention of deficiencies (3, 8-10).

The American Dietetic Association (ADA) was founded in Ohio, October 1917, by a visionary group of dietitians. Led by Lenna Cooper and Lulu Graves, these early pioneers were committed to help the government to conserve food and to improve the public’s health and nutrition during the First World War. The association also established educational standards recommending a two-year college degree for dietitians. In 1921, this requirement changed to a four-year college degree, and the two-year course became known as “assistant dietitian”. Subsequently, in 1928, a bachelor’s degree in food and nutrition followed by 6 months of supervised practice was established as the minimum training for an entry-level dietitian (10).

Shortages of dietitians in the 1940s required the training of dietetic aides who could assume some of the routine daily tasks of the dietitian. Moreover, the work of dietitians who served during the Second World War facilitated international relations and exchange of information. Global dietetics was born and interestingly, according to the report of the ADA Foreign Students Advisory Committee of 1949, the first foreign graduate of a dietetics program to come to the US and complete a dietetic internship and obtain further education in the US was from Argentina (10).

The profession continued to evolve with the setting of standards for both education and practice, the implementation of a code of ethics, and registration and licensure. It was in 1969 when the ADA instituted a system of national professional registration in order to protect the public by identifying knowledgeable and skilled practitioners. Through this system dietitians who met certain requirements started to be designated registered dietitians.

Pedro Escudero (1877-1963), a recognized physician from Argentina, is considered the founder of the profession in Latin America. In fact, in order to recognize his contributions to the field, most Latin American countries celebrate Nutritionist’s Day every August 11th, the day he was born. Dr. Escudero visited many institutions both in the US and Europe and selected from them what he felt suited the needs of Argentineans. He created the National Institute of Nutrition in 1928 and the School of Dietetics in Buenos Aires in 1933. The dietetics program transcended the borders of Argentina giving scholarships for each country of the region, in such a way that the first dietitians of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Panama, Peru and Uruguay, had graduated from the Argentinean school. Afterward, each country created its own school according to their individual needs (4,5).

The Argentinean Association of Dietitians and Nutritionists-Dietitians (Asociación Argentina de Dietistas y Nutricionistas-Dietistas) was created in March of 1947 by a group of 50 professionals with Lydia Pertusi Esquef and Margarita Santamaria as leaders. Despite obstacles (such as the unknown character of the profession and the challenges of incorporating it into the health system) the association was born with the spirit to represent and support the dietetics profession and to promote the continuing education of its members (6).

In 1966, the Pan-American Health Organization, regional office of the World Health Organization, held the first conference in Education of Nutritionists-Dietitians in Latin America, where the designation “Nutritionist-Dietitian” (Nutricionista-Dietista) was introduced. In 1968 the studies were extended from 2-3-year training program to a 4-year university degree, the course curricula was modified, and an internship was included. In 1985, the curriculum was updated, and the professional title was changed again into the current Licentiate in Nutrition (Licenciado en Nutrición) (4).

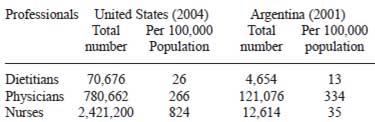

The majority of dietetic professionals in the US are registered dietitians (RDs) and 77% of them are members of the American Dietetic Association (11). In 2004, there were 70,676 RDs (12). To be an RD, an individual must complete a minimum of a bachelor’s degree along with an internship of at least 900 hours accredited by ADA’s Commission on Accreditation for Dietetics Education and pass the national credentialing examination. Dietetic professionals also include the dietetic technician registered (DTR), a two-year credential established in the early 1980s that involves the same threeprong approach of education, experience, and examination (13). There are currently more than 80,000 dietitians and dietetic technicians registered with the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR), the credentialing agency for the ADA that also oversees continuing professional education in order to maintain registered status (14).

The ADA and CDR periodically conduct Dietetics Compensation and Benefits surveys, for the major dietetics practice areas (15). The 2007 Survey reports that 55% of RDs hold primary jobs in clinical nutrition, 11% in community nutrition, 12% in food service management, 11% in consultation and business practice, and 6% in education and research (11). By the end of the 1990s, many professionals had shifted their practice from clinical and community nutrition to marketing, food service and consulting in business practice or in long-term care facilities (2, 16). However, work settings for RDs have changed little since 2002 (17). The scope of practice and responsibilities of dietetic professionals in the US are also affected by regulations at federal and state levels, facility accreditation, workplace policies and procedures, and professional credentials (18).

Over the past two decades interest in developing clinical specialties arose to ensure better patient nutrition care (19). As a result, specialty certifications and credentialing became available in diabetes, nutrition support, renal nutrition, sports dietetics, pediatric nutrition, oncology nutrition and gerontological nutrition. A Certificate of Training in Childhood and Adolescent Weight Management and a Certificate in Adult Weight Management are also offered for RDs and DTRs. Furthermore, a subset of RDs appears to be interested in obtaining advanced practice competency and enrolling in professional clinicallybased doctorate degrees in nutrition (20).

The ADA has recently presented the Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Model, a systematic process designed to improve the consistency and quality of individualized care and the predictability of the patient/client outcomes. There are four steps in the process: Nutrition Assessment, Nutrition Diagnosis, Nutrition Intervention, and Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation, with a profession’s unique and standardized language defined for the last three steps. Since its development in 2003, the ADA has developed several publications describing the NCP. CDR has incorporated the model in several online self-assessment and training modules, and the model is currently being implemented not only nation-wide but internationally. Organizations such as the Dutch Dietetic Association and the Australian Dietetic Association are evaluating the utilization of the Nutrition Diagnosis terminology (21-25).

In contrast to the US, in Argentina and in many other Latin American countries, the term dietitian (“dietista”) is no longer used. The health professional expert in food and nutrition comparable to the RD is the Licentiate in Nutrition (“Licenciado en Nutrición”). In Latin America, “nutritionist” is considered a broader term that accurately covers the wide scope of practice: clinical nutrition, food service management, community nutrition, education and research. To be Licentiate in Nutrition, an individual must complete a four or five-year college degree that includes 750 hours of supervised practice. In 1995 the career was offered only in six universities nationwide, started to grow in the late 1990s, and today is being taught in 21 institutions. Few schools offer a two-year-degree in dietetics comparable to the DTR career, but there is no consistency in its title designation or practice regulations.

Unlike the US, there is no registration examination to become Licentiate in Nutrition. It is the federal government through the Department of Health that issues the license for legal practice (26-27). Although lifelong learning is encouraged for professional development, there is no formal requirement for continuing education. Several post graduate courses are available with opportunities for specialization, but no official certifications have been established at this point. Licentiates in Nutrition may apply for a unique post graduate program: the Nutrition Residency (28). This program, created by a group of dietitians in 1988, consists of three years of supervised staffing in an extensive range of areas, both in clinical and community nutrition. The residents are also supported to perform research and the residency may include opportunities to travel overseas for further professional enrichment.

In 2001, the number of dietitians in Argentina was 4,657, representing a ratio of 13 dietitians/100,000 population (7), which is half the number of dietitians when compared to the US (Table 2). According to a survey made by the ADA for the XIIth International Congress in Dietetics held in 1996, 70% of the Argentinean dietitians worked in hospital settings or for companies that provided services to hospitals (2). Of note, this number does not distinguish between hospital food service dietitians and clinical dietitians, and there is no more recent report to explain the practice settings for Argentinean dietitians. In the US, clinical nutrition services are provided by RDs, DTRs, and nutrition assistants. In contrast, Argentinean dietitians perform many tasks that in the US are done by dietetic technicians or assistants, with the clinical dietitian’s responsibilities being more closely linked to meal services. This could be related to both shortages of dietary and nursing assistance in patient food selection and in assessment of meal intake. As mentioned before, some dietetics schools offer technical degrees, but it is uncommon to find technicians in hospital settings at this time.

The Argentinean Association of Dietitians and Nutritionists-Dietitians (AADYND) has a strong involvement in nutrition health promotion, food certification programs, and continuing professional education. In a similar way to the United States, in November 2000, AADYND published the Dietary Guidelines for the Argentinean Population. And, similar to the US Food Guidelines “My Pyramid”, the guidelines have been graphically translated into an educational tool that is used to address the nutrition problems, food habits and availability of food products in Argentina and to promote good nutrition to the public (29-31). AADYND is also a member of the Argentinean Federation of Graduates in Nutrition (Federación Argentina de Graduados en Nutrición), an organization that brings together 15 dietetic Argentinean associations and is a member of CONFELANyD (Latin American Confederation of Nutritionists and Dietitians) and CONUMER (Committee of Nutritionists of the Mercosur) (32). The Argentinean Society of Nutrition (Sociedad Argentina de Nutrición) and the Argentinean Association of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition (Asociación Argentina de Nutrición Enteral y Parenteral) are also vital organizations in the field.

The evolution, training and work settings of nutrition professionals throughout the Americas are diverse, and influenced by the needs of individual countries and available opportunities. The different cultures and socioeconomic makeup of each nation create different expectations of dietetic professionals and a more established profession is found in economically advantaged countries in comparison to those less developed (1). Dietetics across the western hemisphere is a profession in different stages of maturity, but with growing globalization, the nutrition problems and professional trends are similar between countries. Many factors that are common to both nations will affect the professions growth and status, challenge the dietetics profession and provide unique – yet similar - opportunities in each area. The aging population, increasing consumer expectations, technological revolution and restructured health care systems are some of them (16). This is an opportune time for food and nutrition experts to exchange information and to work collaboratively to solve complex issues, and emerging communication technologies can readily support this.

The future for the profession seems to be promising and world dietetic experts should come together to make the most of the upcoming opportunities. In Argentina, the health care profession that showed the largest growth was Nutrition, with a 159% increase in the number of Licentiate in Nutrition graduated between 1998 and 2002. Although no research has been performed to determine the factors that caused this increase, some specialists argue that this could be explained by an emergent interest in healthy lifestyle and body image as well as increasing incorporation of dietetic professionals in multidisciplinary teams for prevention and treatment of nontransmittable chronic diseases (7). Trends and possible implications for the work of US dietetic experts are described in the Report on the 2006 Environmental Scan for the American Dietetic Association. According to this report, more practice opportunities in geriatric specialties will be available; professionals are needed to study changes in (hectic) lifestyles and to identify and address their impact on nutritional status; new technologies will be used to communicate with patients; and dietitians will be needed to develop products and services that can make use of new findings in genetics and nutrigenomics (33).

Developing effective strategies to prevent and treat obesity also offers opportunities for dietetic professionals as part of multidisciplinary teams (34). According to the World Health Organization, obesity is one of today’s major public health problems and due to its increasing occurrence in both developed and developing countries a new term has been created to describe it, “globesity” (35-36). In the US the number of overweight children has doubled and the number of overweight adolescents has tripled since 1980, and an estimated 67% of US adults are either overweight or obese (37-38). Obesity-related non-transmittable chronic diseases associated with modern lifestyles are also becoming public health problems in Argentina and in other Latin American countries, as the population experiences a significant reduction in physical activity and an increase in energy dense diets (39-42). A paradox that links food insecurity and overweight is another common problem between Latin American countries and the US. There is a growing prevalence of obesity in lowincome groups, who consume more high-carbohydrate/highfat foods in detriment to low-fat dairy products, fruits and vegetables. It was observed that energy-dense foods are not only the least expensive but also the most resistant to the US economic inflation (43). The prevalence of underweight in Argentinean children is decreasing, and it is common to find both under- and overnutrition in the same household (one member overweight and another underweight) or even in the same individual (growth stunting with concurrent overweight) (44,45). Furthermore, the 2007 National Nutrition and Health Survey administered by the Argentinean Department of Health found that the main nutritional problems in young children, women of fertile age, and pregnant women are overweight and obesity (32% of children and 37.5% of women), growth stunting, anemia and iron deficiencies (46). Although nationwide food availability is sufficient to meet the energy needs of the population, imbalances in energy and in micronutrients are significant among low-income families. The nutritional pattern in Argentina is complex, and there is a need for redistribution measures as well as food programs targeted at the most vulnerable groups (47).

Dietetic practitioners in both countries are the professionals responsible for identifying the population’s nutrition problems. They are also uniquely positioned to educate policy makers and to develop effective nutrition programs to promote appropriate dietary habits both in poverty and in wealth. Through collaborative research, and sharing of experiences and effective programs, successful interventions may be expedited.

In summary, even though regional differences exist, it is remarkable that future challenges for the dietetics profession are similar between Argentina and the US. These include:

These common nutrition issues offer a unique opportunity for networking between colleagues from the two nations, either via emerging Internet technologies (48) or by exchanging personnel such as students, practitioners and faculty. Fortunately, over the past half century, linkage between dietetic leaders from diverse countries has been established through international organizations such as the International Confederation of Dietetics Associations (ICDA) and the American Overseas Dietetic Association (AODA) (49-50). Further study through global surveys for dietetic professionals is recommended in order to obtain more information about the similarities and differences in dietetics on an international level and to find ways for dietetic leaders to unite the profession in the battle against world health problems. By working together, the profession can advance the science and share strategies to meet local and international needs. In the end, global alliances among food and nutrition experts can support and strengthen the dietetics profession in the Americas and around the world and help foster partnerships to address the worlds emerging nutrition challenges.

Recibido:10-12-2008

Aceptado: 15-04-2009