This study aims at assessing children’s awareness towards branded food products in central Mexico. One-hundred and twenty children, aged 3-10 years and balanced by gender, were recruited in San Luis Potosí. Kids’ heights and weights were measured in order to calculate their BMI. A cross-sectional questionnaire was administered to children’s parents in order to gain socio-demographic information. Children’s brand awareness was assessed using the IBAI (International Brand Awareness Inventory). Basic exploratory analyses were performed for samples’ general characteristics, and ANOVA was adopted for investigating differences between the IBAI tasks. Results demonstrated that 50% of kids correctly associated the logo to the respective brand in more than 70% of the cases. About half of the sample recalled the right name of the food type in 50% of the cases. 50% of kids recognized the brand name in less than 20% of cases. Older children (7-10 y) showed a higher brand awareness when compared to younger ones (3-6 y). Children demonstrated a consistent knowledge of famous fast-food and snack products. Prevention through informative campaigns should make parents more aware of the TV contents, their kids are exposed to.

Key words: Brand awareness, children, weight gain, Mexico.

Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar la conciencia de los niños hacia los productos alimenticios de marca en México. Ciento veinte niños, de entre 3-10 años en grupos equitativos por sexos, fueron reclutados en San Luis Potosí. Se midieron la talla y los pesos de los niños con el fin de calcular sus IMC. A los padres de los niños se les entrego un cuestionario transversal a fines de obtener información socio-demográfica. El conocimiento de la marca de los niños se evaluó, mediante el uso del IBAI (Inventario Internacional de conocimiento de la marca). Se realizó un análisis exploratorio de base para obtener las características generales de la muestra y se adoptó un anova para investigar las diferencias entre las tareas ibai . Los resultados demostraron que el 50% de los niños había asociado correctamente el logotipo de la marca respectiva en más del 70% de los casos. Aproximadamente la mitad de la muestra recordaba el nombre correcto de marca de alimentos en el 50% de los casos. 50% de los niños reconocía el nombre de la marca en menos del 20% de los casos. Los niños mayores (7-10 años) mostraron una conciencia de marca más alta si se compara con los más jóvenes (3-6 años). Los niños demostraron consistentemente tener conocimiento de los productos de comida rápida y bocadillos más conocidos. La prevención a través de campañas informativas debería conscientizar a los padres sobre los contenidos de televisión a los que que sus hijos están expuestos.

Palabras clave: Conocimiento de la marca, niños, aumento de peso, México.

Unit of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Public Health, Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padova, Italy. Prochild ONLUS Trieste, Italy. University of Monterrey, Mexico.

University San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Department of Nutrition, University of Buenos Aires and Food and Diet Therapy Service, Acute General Hospital Juan A. Fernàndez, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Cuarto Centenario, San Luis Potosí, Mexico

The growing epidemic of childhood overweight and obesity is a major public health concern. Multiple factors influence eating attitudes and food choices of children, like advertising (1, 2), branding (3), peers judgments (4, 5) and social context (6). Such factors need to be evaluated when considering behavioral influences, in order to assess proper public intervention to reduce the international increase in childhood nutrition related diseases.

Genes and environment interact influencing phenotypes for intake and expenditure (7), thus indicating the need to provide information about behavioral aspects influencing obesity’s rise (8). Although genetic factors play a fundamental role in obesity development (9), the rapid increase seen within the last 50 years cannot be attributable exclusively to etiologic causes (8). The “toxic environment” has been recognized as one of the leading risk factors in childhood obesity (6), a representing a scenario where kids are highly stimulated by food-related media messages and encouraged to consume high-fat, high-sugar foods (10, 11).

Food preferences appear just at an early age and are developed all along people’s lifetime, becoming important determinants of food intake first in children, then in adolescents, and finally in adults (12). Many factors, as availability, accessibility, familiarity and parental modeling, influence the process (13).

Children, who exceed daily energy intake levels and present scarce frequency of regular physical activity, are considered being at a higher risk of increasing their body mass (7, 14). By means of an experimental assessment it would be possible to access the behavioral and motivational patterns, promoting compulsive consumption of highly energy-dense foods, which are commercialized on tv broadcasts and other advertisement sources (15, 16).

When considering emotions and choices behind food consumption, brand awareness and frequency of exposure to advertising have traditionally been indicated as conditioning children’s tastes, diverting their preferences towards highly energetic food (1, 17).

It has been estimated, indeed, that children are exposed to 10000 advertisements for food per year, 95% of which are for fast foods, candy, sugared cereal and soft drinks (11). From a recent study developed in toddlers, daily caloric requirement exceeded in energy intake from 10 to 30%, mostly due to energy-dense food consumption (18).

Although present trends show an increasing pressure on food industry’s advertising campaigns to divert children’s preferences towards less processed food, the association between brand awareness, advertising and obesity has not yet been proved (19, 20).

Moreover, little focus has been directed towards the relationship between children’s food intake and energy expenditure (21). The aim of this research was to develop an instrument to assess Mexican chidren brand awareness (the IBAI (International Brand Awareness Instrument)), based on a former research conducted by Forman et al. (3).

Research population consisted of 120 children, recruited in San Luis Potosí, the sample of children was equally divided in females and males, and then split into two age groups (3-6, 7-10). The choice to divide the sample into two age-specific clusters emerged from findings of former studies carried out on this specific topic (22- 24). Results of these studies underlined, indeed, that the recalling and recognition performance of children differed according to their age.

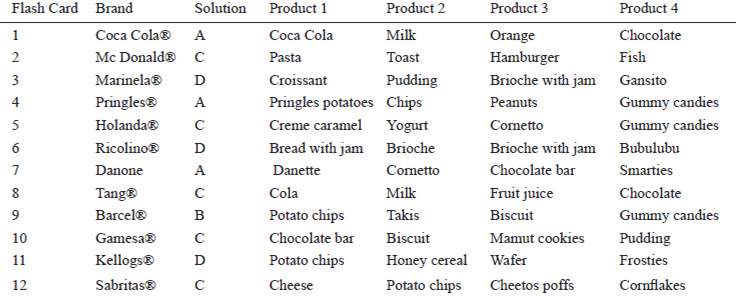

A selection of 12 different brand marks was performed for the mexican specific IBAI version. consistently to what was defined by Forman et al. (3), the IBAI has been adapted to the country-specific context of the present research with special attention reserved to the choice of several food brands, included for this study. Three alimentary lines were proposed as stimuli: sweet foods, savory ones, and carbonated beverages. The choice of these aliments emerged from a constant confrontation among all stakeholders involved within the project (experts in public health, psychologists, educators as well as nutritionists). In order to propose a valid instrument for the context, two basic criteria had to be granted when choosing the single brands: 1.) all products must be available in most Mexican stores and markets on a local as well as on a national level; 2.) all of these trademarks must refer to foods usually consumed by children taking part in this research.

The stimuli consisted of 12 flashcards, containing just a part of a brand mark (e.g. the typical “M” in Mc Donald). In addition, sets of 12 four-image charts were correlated to each flash card. The images in the charts represent different alimentary alternatives (see table 1 for details). Out of these, only one corresponds to the brand partially shown in the flashcards. Figure 1 shows an example of a flashcard along with its multiple-choice image chart.

Children were recruited after lunch in a quiet room inside the school they attend. The same meal was administered to all the kids and they followed the same physical activity patterns.

Afterwards, children were allocated individually in a classroom, and asked to sit on a chair next to a table, where the material was exposed. The kid was set in front of the researcher in order to interact with him and the observation tools (the 12 image charts). Once the researcher explained the procedure to the child, he showed her/him each single card representing a food brand, then the selection of 4 pictures containing alimentary products. First the child was asked to name the specific logo shown on each single card and afterwards she/he was invited to link it to one of the 4 images of aliments. The researcher then assigned 1 point if the child correctly named the product, 1 point if it has been matched to the respective food category and finally 1 point if the kid recognized the specific name of the product (e.g. “Mc Donald” is the brand, the correct image is a double roll containing two hamburgers with cheese, the products name is “Big Mac”).

Brand Awareness Scores (IBAI-score) could range from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 36, with a cut-off set at 16 points, defining two groups: low-brand awareness children (<16) and high brand awareness ones (> 16) [15].

Children who were diagnosed with cognitive disorders, metabolic diseases or allergies were excluded. Parent’s informed consent was obtained for all children prior to each child’s participation in the study, and they were explained the precise aims of the study and was guaranteed anonymity. Treatment of all data was performed in compliance with the guidelines and ethics standards issued by The American Psychological Association (25). Appropriate permission was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards.

A questionnaire was administered either to children than to their parents. The questionnaire was structured into four parts. The first one aimed to assess socio-demographic characteristics of the whole family, asking about parental education, family members’ bmi and composition of the household. A second section, in turn, looked into the general healthstatus of the family, especially eating habits, nursing, chronic diseases, etc. The following section assessed their eating habits in terms of both, quality and quantity of energy intake. The last part considered daily intensity and weekly frequency of physical activity performed by the children.

Children were weighed and measured in light clothing and without shoes on a balance scale and with a body meter measuring tape with wall stop. Weights and heights were utilized to calculate BMI. Children were considered to be overweight/obese with a BMI ≥85th and underweight with a BMI <5th, according to CDC growth standards (26, 27).

Basic exploratory data analysis was performed on the sample and was reported using median (I-III quartile) for continuous variables and percentages (absolute numbers) for categorical variables, whenever appropriate. Throughout a linear regression model the effect of age and gender on the total ibai score was assessed. In order to analyze differences with regard to the three tasks of the ibai (brand recognition, brandproduct association, product recall), anova was adopted for repeated measures.

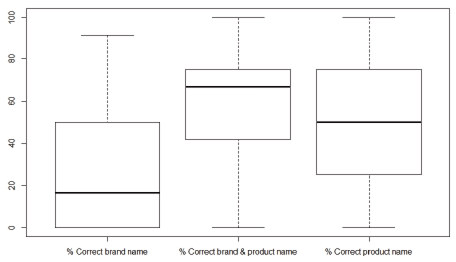

Distributions of correct recognition, recall and matching emerged from the IBAI test are shown through boxplots (Figure 2).

Analyses were performed using the R-software.

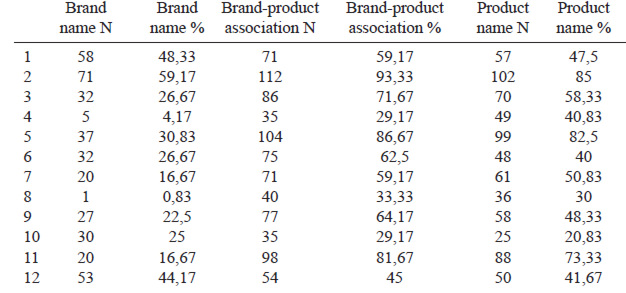

Children’s IBAI scores arising from exact recognition of the brand mark, positive association between the logo and the respective product, as well as correct recall of the specific aliment are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2, instead, shows the different distribution of the single IBAI tasks, where overall 50% of the kids associated correctly the logo to the respective brand in more than 70% of the cases. Around half of the sample recalled the right name of the food type in 50% of the cases. 50% of kids recognized the brand name in less than 20% of cases. This comparison among the single boxplots, representing the main outcomes of the study with the twelve flashcards, shows that the brand-product association task, the brand recognition task and the product recall task show different levels of performance as demonstrated in Figure 2.

With regard to age, results showed that older children (7-10 y) performed better in the recognition task, instead in the recalling and association tasks, when compared to the younger ones (3-6 y). No significant gender related association could be revealed.

In the rapid spread of nutrition related pathologies among children, age-specific advertising has been targeted as positively increasing the phenomenon. A systematic review of all the evidence made available by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) in 2003 (28), and a report by the Office of Communications (Ofcom) in 2004 (29) underlined the urgent need to expand knowledge about the influence of food commercials on children’s eating habits. Both researches concluded that there is a link between the exposure to advertisement and obesity. In a further study, Ashton (30), underlined, instead, that both studies showed evident contradictions. In the first review, a statistically significant relation between a child’s exposure to advertising and a rise of energy intake was found. However, whilst exposure to food commercials did reduce children’s nutrient efficiency, it accounted for only 2% of the variance and had no direct effect on caloric intake, while parental behavior’s influence was fifteen times greater (31). As indicated by Kopelman (32), indeed, both reports appeared to have major limitations, being strongly dominated by studies in North American setting and concentrating only on television advertising, ignoring all other inputs that might influence children’s awareness. Kopelman’s study, held on children from 9 to 11 years, did not demonstrate a close relationship between brand awareness and the children’s reported eating behaviors, food knowledge and preferences, although the English sample showed a high brand logo recognition.

Buijzen et al. stated in a study published in 2008 (33) that television food advertising contributes to an unhealthy diet, influencing not only children’s awareness towards brand-marks, but promoting even more a general rise in consuming energydense foods. Conclusions, however, were derived from correlational data, which do not isolate any specific causes. The same limitation regards also the linkage between branding and obesity.

Brand awareness is defined as the active and passive knowledge of a particular brand. Research on the brand awareness of young children has focused on two aspects of brand awareness: brand recognition and brand recall. The IBAI questionnaire, adapted to the Mexican context, considered both these aspects, by researching not only children’s knowledge of brand recognition, but also of specific product naming.

Former studies, examining toddlers’ and preschoolers’ brand recognition (34, 35) and brand recall (36), showed that children’s ability to recognize brands starts earlier in development than their ability to recall these brands, showing in preschoolers an excellent recognition memory, whereas their recall memory performance is considerably weaker. Moreover, older children have more content knowledge than younger children about almost everything. In general, new information is best learned and remembered when it can be related to existing knowledge in memory, a capacity that is more distinct in older children (37). In brand awareness building, along with normal developmental patterns, environmental factors result crucial determinants.

Brands are recognized by children in early life, but their effect on obesity development has not yet been clarified. By 2 years of age, brand awareness can be detected in children (38), progressively increasing selective attention and association abilities with certain products (39, 40), particularly if brands use salient features such as bright colors, pictures, and cartoon characters (34). Just in pre-school period, preferences towards specific foods start to arise, inducing a behavior defined as “consumption by influence” (41). Marketing strategies, therefore, take into account these phenomena (41), in order to encourage children to recognize and differentiate particular products and logos; for example advertisers place cereal boxes at children’s eye level, because they know that toddlers can recognize brands of cereals, attracting their attention while there are seating in the grocery cart (6).

Previous experimental studies have shown a brand effect on children’s preferences. Robinson et al. (42) examined the effects of cumulative marketing and brand exposure on young children, by testing the influence of branding on taste preferences. Results showed that branding of foods and beverages influenced young children’s taste perceptions, with a significant greater effect in those more highly exposed to TV. Roberto (43) explored the use of licensed characters as taste promoters in children from 3 to 6 years. Such results underlined a positive influence on taste and preferences towards so called junk food. A similar, recent work by Lapierre et al. (44) investigated whether food packaging with licensed media characters affected taste assessment of cereals, revealing consistently to Robinson and Roberto a positive effect of subjective judgments.

Unlike previous studies, focused on younger age groups, our research targeted children between 3 to 10 years old, in order to assess brand-awareness not only within specific groups, but also carrying out a comparison among them. Within our sample, age-related differences appeared.

O’ Cass’ and Clarke’s study (45) showed that main differences between age and gender are evident in types of brands recognized or recalled rather than in the number. In our study, indeed, the older group demonstrated a better performance while carrying out the brand recognition tasks.

Despite age and gender, environmental factors like television advertising exposure, family characteristics, and peer influence determine young children’s brand awareness. Correlational studies on children’s brand recognition have demonstrated a significant relationship between television exposure and brand recognition (34, 46, 47). Some studies suggest that children from high income families show a better brand awareness, because they have greater exposure to the economic world than children of low socioeconomic status (37). Other studies, in contrast, have found that children belonging to low income families are better aware of brands, because they are exposed to the market-place earlier and more extensively than those grown in contexts with high socio-economic background (48).

The study incorporated data from 120 kids, all children belonged to the same Mexican regional context, namely San Luis Potosì, and results could therefore only be intended as contextspecific. Further research should extend the sample to a more cross-regional survey in order to understand if cultural differences in a country, presenting important variances from the north (close to the United States) to the south, where influences of South-American societies exercise a stronger impact, would produce different levels of awareness towards brand marks. Lifestyles and consumption habits are assumed to differ significantly, also due to the geopolitical pluralism of a central American country, which is going through a cultural transition. There was a second limitation, data could only be intended as an aproximate estimation of general trends across the overall population. Direct observation, also via ethnographic methodologies, could integrate the findings of this study with a perspective, naturally situated within real contexts

The study aims to assess, the awareness of 3-10 years old children towards brand marks of certain food products, usually commercialized in supermarkets and fast food franchising within a regional context of central Mexico. Results showed that children demonstrated a consistent knowledge about famous fast-food and snack products and that the awareness towards brands produces major effects in older children. Prevention through informative campaigns, making the parents more aware of the TV contents, their kids are watching, would improve the choice of kid-specific programs, monitoring also the food advertisement they are usually exposed to.

The work has been partially supported by an unrestricted grant from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs under the programs “Programmi di alta rilevanza scientifica e tecnologica” Italia-Messico and Italia-Argentina, and from ProChild ONLUS (Italy).