Adequate nutrition during the first two years is important and ensures an adequate development in the human being. The following research evaluates the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) for children under 5 years old, hosted by Ecuador in 2002. The tool applied was established by the Asia Group of The International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN), which was called the World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi). WBTi establishes a framework for assessing the compliance that a country has made in implementing the Global Strategy, helps key stakeholders plan and make decisions at various levels of action, and identifies the strengths and weaknesses of their policies and programs. The tool was applied in 23 key stakeholders from the main cities of the country and from the governmental and private sectors who were working actively for the Nutrition of Ecuadorian children. They were selected on the basis of their position and experience in the program evaluated and their willingness to participate. According to WBTi, Ecuador’s level of compliance is Low. Three of the ten indicators that evaluated policies and programs scored critically; likewise, two of the five indicators that evaluated practices were scored with a critical score. The deficiencies in complying with the National Policies, Programs, and Coordination showed an important impact on their overall compliance, which, together with a short duration of breastfeeding and the extensive use of bottle feeding, significantly affect the Infant and Young Child Feeding.

Key words: Ecuador, Breastfeeding, Policies, Programs, Practices.

Una correcta nutrición durante los dos primeros años de vida es importante y asegura un adecuado desarrollo en el ser humano. La siguiente investigación evalúo la situación del país y los avances alcanzados en implementar la Estrategia Mundial para la Alimentación de Lactantes y Niños Pequeños (ALNP) (menores de 5 años); acogida por Ecuador en el año 2002. La herramienta fue establecida por el grupo de Asia de la Red Internacional de Grupos Pro-Alimentación Infantil (IBFAN), quien la denominó WBTi -World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative- (por sus siglas en inglés). La WBTi, establece un marco referencial para evaluar el cumplimiento de un país en relación a la implementación de la Estrategia Mundial para la ALNP y ayuda a actores claves a planificar y tomar decisiones en varios niveles de acción, identificando las fortalezas y debilidades de sus políticas y programas orientados a la protección, promoción y apoyo de la Alimentación del Infante. La herramienta se aplicó en 23 actores claves del sector privado y gubernamental, de las principales ciudades del país y quienes trabajaban activamente por la Nutrición de los niños del Ecuador. Los informantes claves, se seleccionaron en base a su cargo y experiencia en el programa evaluado y su voluntad a participar. Acorde a la WBTi, Ecuador tiene un nivel de cumplimiento bajo. Tres de los diez indicadores que evaluaron las políticas y programas de la ALNP obtuvieron un puntaje crítico; por otro lado, dos de los cinco indicadores que evaluaron las prácticas de la ALNP se calificaron con un puntaje crítico. La falla en las Políticas, Programas y Coordinación Nacional mostraron un impacto importante en el cumplimiento global de la Estrategia, las que conjuntamente con una corta duración de la lactancia materna y el amplio uso de la alimentación con biberón afectan de forma importante la alimentación del infante en el Ecuador.

Palabras clave: Ecuador, Lactancia Materna, Políticas, Programas, Prácticas.

https://doi.org/10.37527/2018.68.1.001

1San Francisco University of Quito, 2National Coordinator of IBFAN Ecuador, General Educational Hospital of Calderón. Ecuador.

Adequate nutrition during the first two years of life is of vital importance and ensures the adequate development of the human being. Breastmilk provides optimum nutrition for the infant (1) Moreover, the impact of breastfeeding practices is well documented (2) A delay in the children’s growth has a long-term impact on their physical and mental development and keeps their school learning skills from improving (3) Over recent decades there has been international agreement on key strategies to improve infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices. These are summarized in the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (4) and the Innocenti Declaration (5).

This research assessed the country’s situation in implementing the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding under 5 years old (4), which was hosted by Ecuador in 2002. With the participation of key actors at local, provincial and national levels, it shows the strengths and weaknesses that prevail in the implementation of Child Feeding Practices, Policies and Programs; and establishes strategies that seek to protect, promote, and support the Infant Feeding in Ecuador.

This study is cross-sectional and descriptive. It analyzed quantitative and qualitative information of Infant and Young Child Feeding. It was carried out during the months of September to November of the year 2015 through the participation of 23 key actors selected on the basis of their position and experience in the program evaluated and their willingness to participate. All of them were working actively for the Infant Feeding in the Ministry of Public Health, the Local Health Directorates, the Coordinating Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion, the Cooperation Agencies of the United Nations System, and Ecuadorian Institutions of Higher Education.

Through personal interviews, the International tool “World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative” (WBTi), was used to collect the information (6, 7). WBTi was created to establish a framework for assessing the compliance of a country in implementing the Global Strategy at the national level. This tool helps key actors to plan and make decisions at various levels of action, identifying the strengths and weaknesses of their policies and programs aimed at protecting, promoting and supporting appropriate infant feeding practices. Over 90 countries have used the WBTi toolkit (8).

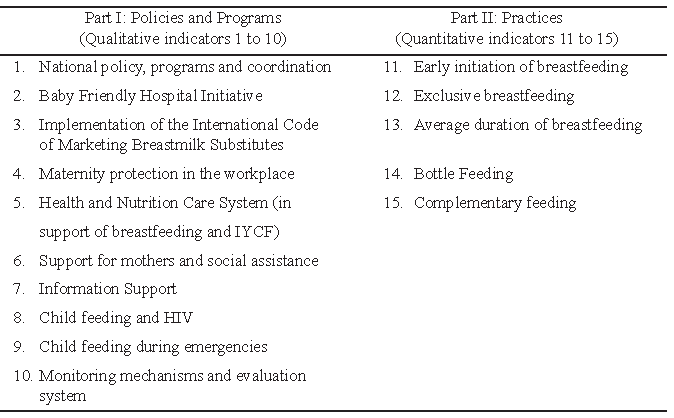

WBTi recommend analyzing 15 indicators divided in two parts, as shown in (Table 1). Part I correspond the qualitative indicators and refers the policies and programs, for which 10 indicators was identified. They are based on the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (1). This section was used to gain a better understanding of what factors influenced the programs and practices. In part II, 5 additional quantitative indicators were analyzed to assess the practices of the Infant and Young Child Feeding. A total of 15 indicators was compiled and analyzed in this research.

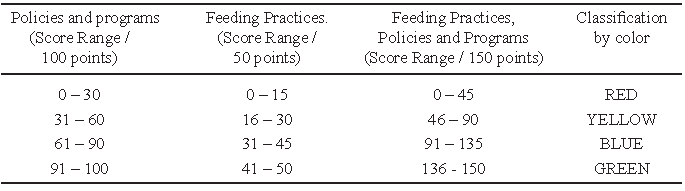

Each indicator was addressed by the following components: 1) The key question to be investigated; 2) Background on why the program’s practice, policy or program can be important; and 3) A list of criteria across a subset of questions that need to be addressed to identify areas for improvement and to identify the achievements the indicator has attained. For qualitative indicators, additional methodology such as in-depth interviews, review of information, and bibliography provided by several public and private institutions were used, which are directly related to the topic of the indicator under study. Finally, each indicator was quantified and classified within a range of colors (red, yellow, blue or green) to show levels of compliance. The red color indicates the lowest compliance and the green color, the highest compliance (1) (Table 2). Since each indicator had a specific meaning, this research allowed us to identify the achievements, weaknesses and shortcomings in relation to the Global Strategy in the policies, programs, and practices that are in force in the country.

Score assigned to indicators: Each indicator is rated on a 10-point scale. The sum of the indicators is analyzed independently for qualitative and quantitative results. For qualitative indicators a set of 10 indicators were analyzed and assigned a maximum score of 100 points. For quantitative indicators a set of 5 indicators were analyzed and had a maximum score of 50 points. The total sum of the indicators reached a total of 150 points.

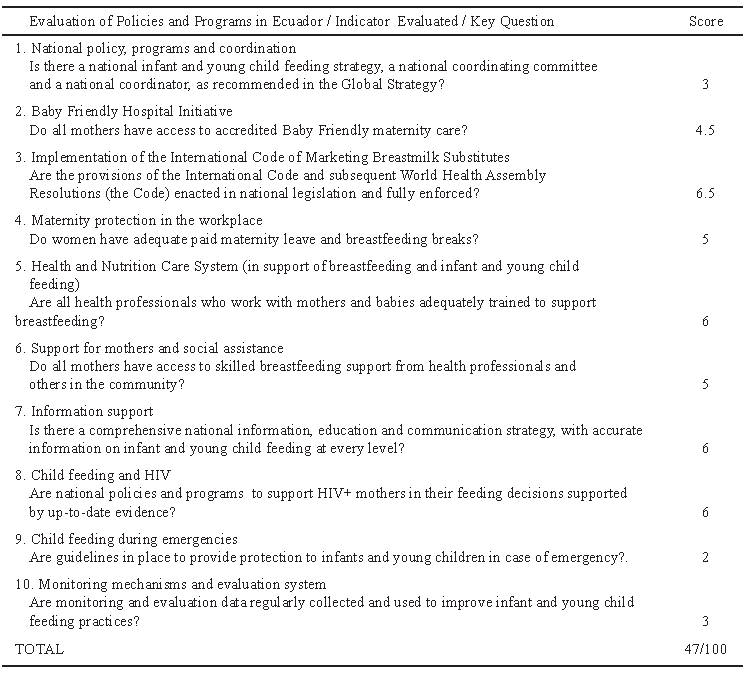

WBTi allowed identifying the strengths and weaknesses of Ecuador in relation to its policies, programs, protection practices, promotion and support of the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. The score of each indicator were extracted in Table 3 and 4. For Ecuador, the policies and programs (qualitative indicators) of Infant and Young Child Feeding showed a level of compliance of 47/100 points (Table 3).

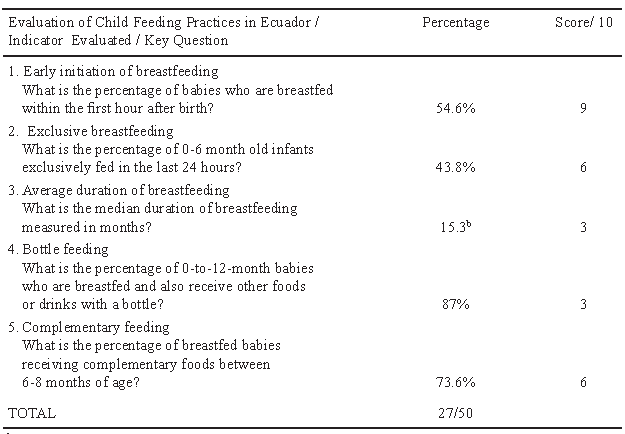

When assessed the practices (quantitative indicators), the country showed a compliance level of 27/50 points (Table 4). According to the WBTi, both scores ranked a low level of compliance. Finally, the overall score of the 15 indicators is calculated on a basis of 150 points, attributing to Ecuador 74 points, which again classified a low compliance of the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding in Ecuador.

This is a central indicator of the country’s implementation of the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, because it outlines the guidelines and strategies to achieve the objectives set. Ecuador has a national development plan 2013-2017 (9) in which one of the indicators state to increase in 20% the Exclusive Breastfeeding Score. Several strategies had been developed for its action and execution; however, this policy was not monitored or evaluated periodically, thus limiting the perception of its progress.

It is advisable to follow the recommendations published by UNICEF and IBFAN, whom states that the National Policies must be accompanied by a detailed action plan that precisely defines the objectives, schedule, distribution of responsibilities and indicators for future monitoring and evaluation (10). Moreover, the discontinuity of the strategies and their managers is added to these limitations. The primary health and nutrition sectors are poorly linked. They are prone to politicization and refer little attention to the measurement of their results (11).

In 1991, WHO and UNICEF announced Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, which was revised, updated, and expanded for comprehensive care in 2008 (12) with the aim that the hospital services and maternity hospitals adopt friendly practices that promote, protect, and support breastfeeding. In Ecuador, several efforts had been made to ensure that health services achieve this certification, nevertheless, this effort was not consolidated and most of these hospitals lost their certification. It is recommended to create a body responsible for periodically monitoring and evaluating the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative at the national level, in order to promote and monitor the continuous implementation of the steps for successful breastfeeding (12).

The promotion of breastmilk substitutes by manufacturers and distributors continues to be a substantial global barrier to breastfeeding. The Implementation of the International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes (13) in Ecuador has a compliance level of 6.5 points according to WBTi, and it showed that in Ecuador it is necessary to determine who can be the actors of the Ministry of Public Health, other governmental, and private sector institutions that pursue and work for its application.

This article proposes a practical guide, which establishes the procedures to denounce noncompliance of this task, which should be freely available to the community. Health personnel (doctors, nurses, nutritionists, etc.) as well as points of sale such as pharmacies and supermarkets need to be trained of this International Code to avoid infractions and generate a higher compliance with this indicator. Finally, it is necessary to update the legislation and regulations in force to successfully implement the recommendations given by The International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes and its subsequent resolutions.

In Ecuador, there is a poor implementation and socialization of the laws and resolutions of maternity protection. These are inalienable rights for pregnant women and lactating mothers who have a legal, steady job in either the public sector or the private one. However, only 31.5% of productive women in the country have a legal, steady job (14) and the rest corresponds to the informal sectors of the economy who do not have these labor benefits. The Ministry of Labor is the body in charge of monitoring compliance with the law; however, it lacks the enough personnel to carry out a systematic monitoring of its compliance, which increases the rate of violations of this right.

The Innocenti Declaration updated in 2005 (15) called for urgent attention of working women in the non-formal sector, and further monitoring of its application consistent with Maternity Protection Convention No. 183, 2000 and Recommendation 191 of the International Labour Organization (ILO), which encourage facilities for breastfeeding to be set up at or near the workplace (16).

Because the mothers contribute to the family income and job security, employers’ long-term profits, and a nation’s socioeconomic health and stability, we strongly recommend, implementing facilities for express and storing breastmilk at their workplace. See indicator 6, this topic is addressed more broadly.

The Ministry of Public Health created a series of technical standards for the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, aimed at the health personnel of the first level care units; however, the message has been poorly spread at the national level. Consequently, the health professionals do not know about the Global Strategy and their components. It is recommended to develop a continuing education system that provides regular training in an upto-date way for the personnel (administrative and healthcare workers) who serve the first level units. Standardize the academic curricula in the area of nutrition and child nutrition of the health professionals it’s propose as one of the strategies to improve this indicator.

Ecuador has standards of care (in counseling and support areas) for pregnant women. In spite of this, support for mothers and community social assistance aimed at protecting, promoting, and supporting optimal infant and young children’s feeding are weak. As a result, care for morbidity is prioritized. High demand, with undefined responsibilities among professionals, makes it difficult to carry out an adequate follow-up and demand compliance.

Overall, the attendance of pregnant women to the first prenatal check is performed at week 16 for the urban area, and in rural areas of the country, it takes place later than this average (17) Although there are movements that promote vaginal delivery and breastfeeding, these options have been accepted by very few public health services, and in private hospitals, delivery by cesarean section is chosen. Therefore, training primary care physicians and technicians in breastfeeding, maternal and infant feeding, and implementing support groups are key actions to protect, promote and support breastfeeding in Ecuador.

Ecuador has implemented at the national level Human Milk Banks, which become centers to support, protect and promote breastfeeding. The Human Milk Banks, has proved to have a high impact in the reduction of neonatal morbimortality and are services where mothers come for help, to solve doubts and to treat pathology related with the breastfeeding.

Currently Ecuador has 9 services and 3 more services are in the pipeline.

Finally, provide the facilities to safely express, collect and store breast milk at workplace it is strongly recommended. There is a specific entitlement under the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) for both new and expectant mothers. In Ecuador the implementation of breastfeeding support rooms in workplaces where there are more than 20 women of childbearing age is a regulation (24). The Ministry of Public Health to encourage its implementation awarded the company or Institution with a certificate.

The Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador, through the Nutrition Department and the Full-Childhood Project, has developed informativematerials, aimed at informing aspects such as breastfeeding, complementary feeding, micronutrients supplementation, and correct feeding habits for pregnant women and lactating mothers. Similarly, the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion provides several educational actions on this subject for its professionals (nurses) and technicians, who in turn provide care and advise for families with children under 5 years of age through the program (Growing Up With Our Children) (18).

This indicator has a rating of six in compliance and it is recommended to design a comprehensive strategy that puts the nutritional problems of the country, makes communities become involved in their information needs and use appropriate communication channels. Moreover, the mothers prefer breastfeeding promotion aimed at their partners, families and throughout society (19).

Ecuador has national regulations for people living with HIV (which includes pregnant women and nursing infants) (20). However, this regulation is not applied in a generalized way in all the health services of the country; there is a lack of policies and programs aimed at feeding children and HIV; and health providers do not receive adequate training on the subject. This results in poor support, poor counseling and poor postpartum follow-up on the feeding of children born from HIV positive mothers.

With a compliance level of six for the Infant Feeding and HIV Indicator, there is a clear need to determine the current nutritional status of mothers and children with HIV. It is recommended to carry out an evaluation and analysis of the problems in the country in order to establish and implement food policies and programs, update the current norms, and develop strategies that, through scientific advances, allow adequate management of the situation of mothers and children who have HIV (21).

The Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador enacted legislation on infant feeding in emergencies (22) with the purpose of establishing the guidelines for the food and nutrition of families who have been victims of emergencies and disasters. However, this legislation lacks strategies for its application in order to support, protect, and promote adequate nutrition for the infant and young children during emergencies and disasters. This indicator has a rating of two, which expresses the urgent need to develop an inter-sectoral policy to care for nurses, infants and young children during emergencies and disasters, and also to coordinate these actions through the National Secretariat for Risk Management.

In Ecuador nutritional data collected from pregnant women and children under 5 years old, is not processed in the short term, limiting results-based decision making. Although there is a statistical information system, the system shows failures, which prevent monitoring, and evaluating maternal and child nutritional status in the country from being carried out in a systematic way. As a result, consolidation of data from the first level to the national scale is slow, inefficient, and unusable.

It is recommended to decentralize the analysis process of the data generated by provinces, so that at the province level, periodic reports are obtained to allow timely decision making. This will provide correct feedback to make adequate decisions, allowing the country to have highquality and short-term information.

According to the last National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT-ECU) (23), it has been observed that 54.6% of mothers breastfeed their child within the first hour after delivery. However, the following limitations was founded: first, noncompliance and resistance of healthcare practitioners to comply with the care service regulations for both the mother and the child in terms of immediate attachment and breastfeeding during the first hour of the baby’s life; second, the lack of knowledge of the medical community about the advantages for the child and the mother; and third, the scarce infrastructure and equipment of some health services to duly comply with the regulations. It is recommended to implement a monitoring system for the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, along with the necessary conditions to duly comply with the regulations.

In Ecuador, exclusive breastfeeding shows a percentage of 43.8%, being highest in the poorest quintile of the population (23) There is a clear trend between the prevalence of breastfeeding and the level of education of the mother, with the highest practice of breastfeeding with the highest level of education (24). However, in Ecuador this trend is contradictory, and a higher prevalence is shown in mothers without any level of education (17)

The poor support from healthcare services, the lack of targeted information on the importance for the child and the mother and the widespread dissemination and promotion of the bottle feeding and breast milk substitutes are limitations that must be corrected to culminate successfully the period of exclusive breastfeeding. It is recommended to implement and strengthen maternal and child care services through training in breastfeeding and complementary feeding counseling aimed at technicians and healthcare professionals, and to implement adequate control and monitoring of responsibilities that comply with The International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes.

The World Health Organization recommends that breastfeeding at least 24 months and longer; (if the mother chooses so) (4). In Ecuador, the median duration of breastfeeding is 15.3 months, being lower in the urban area (14.5 months) than in the rural area (17.1 months) (23)

Despite, cultural barriers are complex and include the shame of feeding in public (25), these were reinforced, by the poor support from healthcare services, poor community care in breastfeeding and complementary feeding, and the rapid integration of women into work. It is recommended working on breastfeeding promotion strategies, as part of a national program that revalues the culture of breastfeeding, and implementing lactation support rooms in workplaces where there are more than 20 women of childbearing age (26)

The bottle feeding has a great promotion, which weakens the practice of breastfeeding in the country. According to ENSANUT-ECU, 30% of children aged 0-5 months from the poorest quintile receive bottle feeding. Furthermore, as the age advances, the percentage increases. This causes discontinuation of breastfeeding and inappropriate complementary feeding from the baby’s very early ages (23).

It is recommended, the Implementation of the International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes(13) in Ecuador, which include the regulations on the promotion of bottle feeding. And update current Ecuadorian legislation to achieve a successful implementation of its recommendations and subsequent resolutions for its breach.

Complementary feeding should begin when the child reaches 6 months of age, as a complement to breastfeeding, because exclusive breastfeeding does not reach completely the nutritional requirements of the child at the age of 6 months. 73.6% of Ecuadorian children aged 6-8 months started complementary feeding in a timely manner. However, the quality of this food is poor due to an inadequate consistency, quantity and frequency of food offered (23). The same survey also found that about half of the children from the first month of life had already received liquids and /or food, which shows the lack of exclusive breastfeeding until the age of 6 months.

The fact that many Ecuadorian mothers lack knowledge about adequate complementary feeding techniques (quality, frequency and quantity) and the fact that healthcare services offer very little support on adequate techniques of nutritional counseling in complementary feeding are limitations that must be overcome to promote the compliance with this indicator.

This study showed strengths and weakness. We used a standardized tool that allows the comparison of its results with other countries and regions of the world. WBTi is easily accessible as it is available on the web. These characteristics make it a universal tool created to help key actors plan, make decisions, and identify the strengths and weaknesses of their policies and programs. Nevertheless, for our country we found the next limitations: a lack of continuity, of key informants; showed a high turnover rate. The scarce systematic application of the WBTi tool limits the evaluation of the country’s progress, strengths, and weaknesses in the execution of the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding.

Breastfeeding is consistently undervalued. It is a misconception that breastmilk can be replaced (27). The promotion of breastmilk substitutes and its marketing have turned infant formula from a specialized food for babies who cannot be breastfed into a food perceived as normal for any infant (28). Virtually all mothers can breastfeed, provided they have accurate information and the support of their family, the health care system and society at large (29).

The literature has shown that countries that could implemented the Global Strategy have greater breastfeeding rates (8,30). The most important recommendations for each WBTi indicator can be found in the body of this article. However, the failure of National policy, programs and coordination shows a significant impact on their overall compliance. This, along with a short duration of breastfeeding and the extensive use of bottle feeding, significantly affect the Infant and Young Child Feeding in Ecuador. It is recommended to create a responsible body to periodically monitor and evaluate the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding.

The authors wish to thank The International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN), an organization that adopted the tools validated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and The World Alliance for Breastfeeding (WABA).

This action triggered the formation of the World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative. The authors also wish to thank all the Ecuadorian institutions that collaborated: Ministry of Public Health, Local Health Directorates, Coordinating Ministry of Social Development, Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion, Cooperation Agencies of the United Nations System, and Ecuadorian Institutions of Higher Education.

Recibido: 01-02-2018

Aceptado: 17-04-2018