,

Jaime Silva Rojas2,

Astrid Caichac3

,

Jaime Silva Rojas2,

Astrid Caichac3  ,

Jacqueline Araneda4,

Waleska Willson Rojas5

,

Jacqueline Araneda4,

Waleska Willson Rojas5  ,

Rodrigo Buhring6

,

Rodrigo Buhring6  ,

Viviana Pacheco7

,

Viviana Pacheco7  ,

Claudia Encina8

,

Claudia Encina8  ,

Danay Ahumada9

,

Danay Ahumada9  ,

Marcelo Fernández-Salamanca10

,

Marcelo Fernández-Salamanca10  ,

Ana Maria Neira11

,

Ana Maria Neira11  ,

Paola Aravena Martinovic12

,

Paola Aravena Martinovic12  ,

Pía Villarroel13

,

Pía Villarroel13  ,

Eloína Fernández13

,

Eloína Fernández13  ,

Jessica Moya14

,

Jessica Moya14  .

.

The Objective is to determine the stages of change in the behavior of university students regarding the purchase of ultra-processed snacks consumed. Multi-center study (14 Chilean universities). The participants (4,807 students)evaluated were applied a survey to determine the stage of change of behavior regarding the purchase of foods with warning signs. The students were evaluated and classified as (a) Nutrition Students, (b) Healthcare-related Students and (c) Other degree Students. More than 90% of the students were aware of the food regulation and knew the warning signs. More than 60% of Healthcare-related and Other degree students are in the stage of pre-contemplation or contemplation regarding purchase intent of sugary drinks, juices, cookies, sweet snacks and potato chips; this value is twice the percentage of Nutrition students in this stages ( Chi2, p<0.001). In conclusion there is a high proportion of pre-contemplation and contemplation with respect to purchase intent among the students. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2020; 70(4): 263-268.

Key words: Ultra-processed, sugary drinks, front-of-package labeling, university students, stages of change.

Determinar las etapas de cambio en el comportamiento de los estudiantes universitarios con respecto a la compra de colaciones ultraprocesadas. Estudio Multicéntrico (14 universidades chilenas). A los participantes (4.807 estudiantes) se les aplicó una encuesta para determinar el cambio en el comportamiento con respecto a la compra de alimentos con sellos de advertencia. Los estudiantes se clasificaron como (a) estudiantes de nutrición, (b) estudiantes del área de la salud y (c) estudiantes de otras carreras.Se evaluaron. Más del 90% de los estudiantes conocían la regulación alimentaria y conocían las señales de advertencia. Más del 60% de los estudiantes de la salud y de otras carreras se encuentran en la etapa de pre-contemplación o contemplación con respecto a la intención de compra de bebidas azucaradas, jugos, galletas, bocadillos dulces y papas fritas; Este valor es el doble del porcentaje de estudiantes de nutrición en estas etapas ( Chi2, p <0,001). Se concluye que existe una alta proporción de pre-contemplación y contemplación con respecto a la intención de compra entre los estudiantes universitarios. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2020; 70(4): 263-268.

Palabras clave: Ultraprocesado, bebidas azucaradas, etiquetado frontal, estudiantes universitarios, etapas de cambio.

https://doi.org/10.37527/2020.70.4.004

Autor para la correspondencia: Jessica Moya, email: [email protected]

Chile is one of the largest consumers of ultra-processed foods at the global level, representing 28.6% of total calorie intake and 58% of added sugars (1-2); in addition, Chile ranks first in the world for the consumption of sugary drinks (3). Ultra-processed foods are ready-to-eat or ready-to-drink formulations.These foods consist of refined substances, with carefully combined sugars, salt, fats and various additives. Ultra-processed foods include sugary drinks, snacks and "fast foods" (4).

There is an increasingly higher group of the population of interest; such as university students; this is explained by the size of university population in Chile, being 1 million students in a universe of 17,574,003 inhabitants (5). These students prefer to consume ultra-processed snacks above a different type of food (6).

Consumption of ultra-processed snacks has been related to weight gain and non-communicable diseases (7). During their time at university, students take responsibility for their diet for the first time and usually consume these foods in greater quantities; therefore, this is a critical period for the development of habits that will have an impact on their future health (8).

In response to the high consumption of ultra-processed foods, the Law 20,606 about “Food nutritional composition and food advertising” was formulated in Chile. This law has 3 main concepts: (a) Ban on the sale of ultra-processed foods in schools, (b) Ban on advertising aimed at 14 years old and younger and (c) Mandatory front-of-package warning labels, in accordance with Decree 13/2015 (9). Front-of-package labeling consists of 4 black octagons with white letters; these figures warn about the presence of 4 critical nutrients (calories, saturated fats, sugars and sodium). Despite this law was implemented for the first time more than one year ago, there has not been an assessment of the changes in the behavior of university students regarding the ultra-processed snacks they frequently consume. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the stages of change in the behavior of university students regarding the purchase of ultra-processed snacks consumed usually during their study hours.

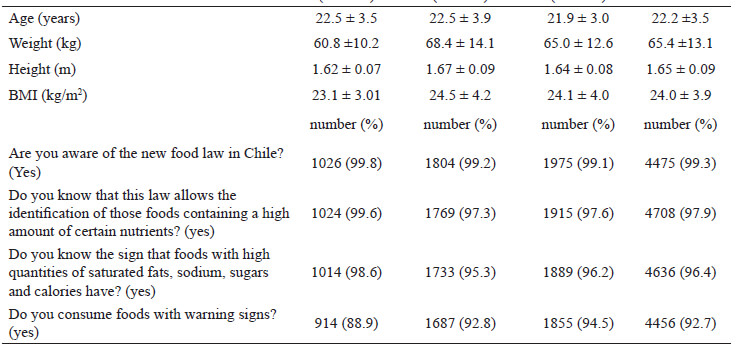

For this analytical, cross-sectional and multi-center study, researchers surveyed students using Google Forms; participants belonged to 14 universities with headquarters in Northern, Central and Southern Chile. In order to calculate the sample size, the population of university students in Chile was used as a reference. The confidence level was set at 95% with an error rate of 3%; the result was a sample of 1,067 students (the final sample consisted of 4,807 students)(Table 1). Every participant was asked tosign an informed consent form before the interview. The time of application of the questionnaire was 1 month. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Facultad de Ciencias Para el Cuidado de la Salud de la Universidad San Sebastian. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Inclusion criteria were: university students aged 18 to 40, male or female, Chilean. Exclusion criteria were: people who did not agree to be interviewed, had a visual impairment or were receiving nutritional treatment.

Each subject was asked about his/her gender, age, weight, height and his/her plan of studies, being classified as (a) Nutrition Students, (b) Healthcare-related Students and (c) Other degree Students. During the second part of the interview, participants were asked if they consumed snacks with warning signs; 10 mass consumption foods with 1 or more warning signs were chosen for this item (sugary drinks, juices, sweet cookies, sweet snacks and potato chips). If the person was a consumer of the snacks with warning signs, researchers asked 2 questions related to his will to change his behavior: (a) Having scores ranging from 1 to 10 (being 1 not important at all and 10 very important), Which is the degree of importance for you to stop consuming certain food?; (b) Having scores ranging from 1 to 10 (being 1 not confident at all and 10 very confident). How confident do you feel about stoppingthe consumption of certain food?. Questions a and b were adapted by Fleta Y. and Gimenez J. from the model created by the American College of Sports Medicine and the classical Prochaska model to assess the stages of change, using the variables confidence and importance that are part of motivation (10,11). Recently, scales for assessing importance and confidence have been recognized by the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics as being very effective in achieving changes in eating behaviors (12). Scores obtained are crossed in a grid to determine the stage of change of the subject. Pre-contemplation: the subject does not intend to change his/her behavior. Contemplation: the person expresses interest in changing his/her behavior and adopting a new habit, but within the next 6 months. Preparation: The person is willing to adopt a habit within the next 30 days and has also incorporated certain habits or isolated actions leading to change his/her behavior. Action: The person adopted a behavior less than 6 months ago. Maintenance: The person has maintained the behavior for more than 6 months. The final classification is obtained by combining the two scales, therefore, the score required to diagnose each stage must reach a minimum in both scales: Pre-contemplation: 1 to 3 points; Contemplation: 3 to 6 points; Preparation: 6 points; Action: 7 points; Maintenance: 9 points.

The frequency (expressed as percentage) and confidence interval for the parameters and stages of change for each of the components are described in this study. Comparisons were made according to gender and nutritional status; significance for categorical variables was determined using Chi square test. Researchers used SPSS Statistics 22.0 software package and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 4,807 students were evaluated (71.6% female); average age was 22.3 ± 3.5 years old. More than 90% of the students were aware of the food regulation and knew the warning signs.

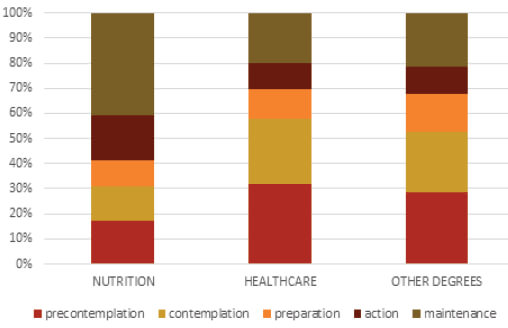

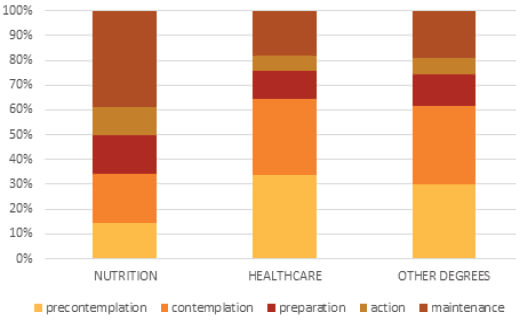

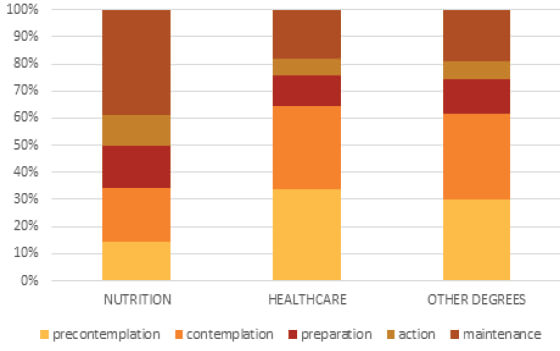

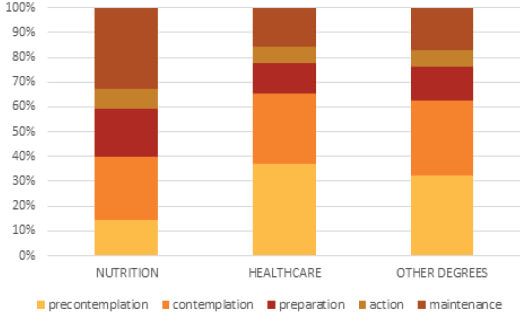

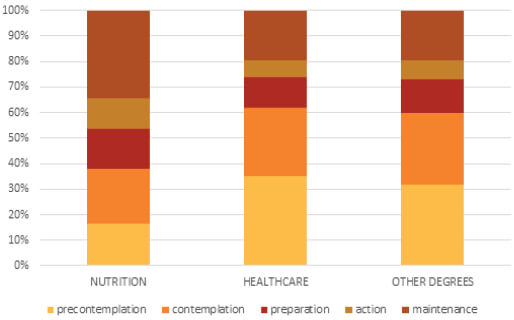

Figures 1 to 5 show the comparison of the stages of change regarding the purchase of sugary drinks, juices, cookies, sweet snacks and potato chips according to the subject’s plan of studies. It was noted that more than 60% of the students of Healthcare-related and Other degrees are in the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages; this value is twice the percentage of Nutrition students in this stages ( Chi2, p<0.001 for all foods), except for sweet snacks and potato chips, with a percentage of 40% in the stages of pre-contemplation and contemplation. Regarding the Preparation stage (Figures 1 to 5) the value is nearly 10%; in Nutrition students is nearly 15%.

Finally, in the Action stage the percentage is lower than 5% in students of Healthcare-related and Other degrees, and in Nutrition students is equal to or greater than 10%. In addition, for all the afore mentioned foods, Nutrition students were in the maintenance stage to a greater extent.

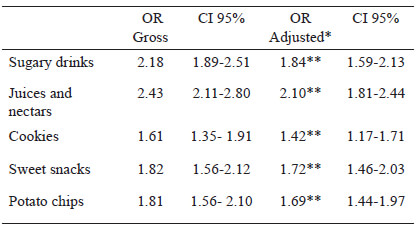

Table 2 shows the reasons for disparity (OR), noting that while being in the stages of action and maintenance, the highest probability of consuming unhealthy snacks belonging to a non-nutrition related degree (OR>2) is related to the intake of juices and nectars (OR=2.10; IC 95%= 1.81-2.44; p<0.001). The rest of the snacks studied are also more likely to be consumed among students of degrees not related to nutrition.

The main result of this study shows that students (mainly from Healthcare-related degrees and Other degrees) are in the pre-contemplation or contemplation stages, that is, they are not willing to make a change in the short to medium term in respect of the purchase of the evaluated snacks.

Different studies have showed that Nutrition students have a healthier diet than those studying other degrees (13, 14). It is usually thought that students of healthcare-related degrees would have a similar profile; however, their behavior is similar to the one exhibited by students of other degrees not related to healthcare (Engineering, Education, Law, Architecture, etc.).

It is interesting to note that from all the afore mentioned snacks, only liquid foods offer alternatives without warning signs, because sugar has been replaced by non-caloric sweeteners that are heavily consumed in Chile, as different studies involving university students show (15-18). Instead, solid foods, especially cookies, contain very little moisture and a significant amount of added sugars and fast (therefore, these foods have a higher chance of having three warning signs: high in calories, high in sugars and high in saturated fats). Salty snacks and potato chips are highly consumed among students; these foods are marked with the "high in calories" and "high in sodium" signs. In this case, it is difficult for the industry to reduce the amount of critical nutrients in these foods, thus, they will continue to exhibit warning signs.

People of this group should favor the consumption of healthy snacks like water and fruits; the consumption of these foods has been associated with better nutritional status (19), but, in order to promote their consumption, they should be low cost and readily available in universities and unhealthy snacks consumption should be reduced, since their excessive consumption has been associated with obesity and other chronic diseases (20,21) and poorer academic performance (22).

It is worth mentioning that even though Healthcare-related students handle a large amount of information related to healthy lifestyles, they are not able to make these changes themselves (23). This bears out the fact that changes in behavior involve much more than cognitive aspects, and attitudes related to behavior change must be specifically addressed.

Among the strengths of this research we can mention that the sample was representative of the country; among the weaknesses we can point out we did not separate students according to their plan of studies in healthcare-related degrees and non-healthcare degrees, there must probably be some differences. In addition, we could evaluate according to gender and current year of study. Other weakness is that groups were not homogeneous concerning gender, due to the fact thatabout 90% of Nutrition students are female.

A high proportion of Healthcare-related and Other degree students are in the stages of pre-contemplation or contemplation. It is necessary to conduct educational work, especially among Healthcare students, since in the future they will be responsible for giving advice about healthy lifestyles. However, it is interesting to note that Nutrition students, unlike other degree students, are mostly classified in the action and maintenance stages.

Furthermore, they should be trained in knowing the food law, since so far the efforts of the Ministry of Health have been focused on structural measures but there have not been educational measures aimed at generating changes in eating patterns.

Finally, it is necessary to perform follow-up studiesin order to assess the impact of the food law and to know if it has helped in the reduction of ultra-processed foods.

Recibido: 11/11/2021

Aceptado: 10/03/2021